To write this blog post, I got in contact with the research team of the review and the first author, Dr. Anna Sverdlik, took precious time to answer my questions and to review my writing. Anna is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Université du Québec à Montréal, Department of Psychology, working in the field of Social Psychology. Thank you so much Anna for your openness, your time and your inputs! 🙂 Here a few words from her:

“As a doctoral student, I began to witness gradual declines in the motivation and well-being of my peers (and myself) in the doctoral process, and struggled to understand why this was a common experience. When trying to find empirically informed answers, I was baffled by the scarcity of literature focusing on these issues in the doctoral population, which was the drive behind the article reviewed here. We hope that the article will be useful in informing students, advisors, departments, and policy makers where they can spend their time and resources to improve the doctoral experience.

– Dr. Anna Sverdlik”

A few months ago, a scientific team from McGill University (Canada) published an extensive review about the PhD experience, looking at “factors influencing PhD students’ completion, achievement, and well-being” (Sverdlik et al., 2018). To me this review appears like a must read for all academics; not only for supervisors, but also for anyone involved in doctoral education, and, of course, for current PhD students to help them understand their own situation. However, the review, which looked at over 160 publications, is quite long- with 21 pages of text I know deeply that many academics won’t find the time to read it…

Therefore, in this blog post I attempt to summarize this review by highlighting the points which strike me the most. Indeed, many of the points analyzed and described by Sverdlik et al. accurately resonate with my own PhD experience in Switzerland 🇨🇭 and helped me to reflect on it!

Like it had been done before, Sverdlik et al. analyze two types of factors influencing PhD students experience: external and internal factors. Within external factors, the four most influencing ones appear to be: 1) supervision, 2) personal/social lives & work/life balance, and 3) departmental structure and organization, and 4) financial opportunities. While I thought that these factors were introduced in this order to reflect different levels of importance, Dr. Anna Sverdlik made a note to remind my readers and me that every PhD experience is unique, and that the relative importance of each factor varies for every student. Within internal factors, the authors analyzed motivation, writing skills, self-regulatory strategies, and academic identity. Importantly, some of these factors are interconnected, especially students’ motivation which is affected by external factors (see more below).

As this blog post became actually quite long itself, I decided to exclude the following factors: personal/social lives & work/life balance, financial opportunities; and I trimmed through the academic identity part. Also, to improve readability I removed most references to original papers, yup this is my blog not an academic paper.

1. External Factors — Supervision and Departmental Structure

For me who graduated only over a year ago, it is no surprise to read that “[supervision is] considered to be the most influential [factor] in the doctoral experience” (table 2, page 5) but it is still eye opening to read it in a high-quality academic work. Equally interesting for me is to see how, beyond the supervisor, departmental structure is also key for students’ success.

One aspect which is appearing throughout the paper is the lack of communication and the lack of understanding between these three parties: the student, its supervisor(s) and its department. This is particularly clear when looking at papers where students and faculty members were asked about the reasons perceived behind students dropping out of their programs (attrition), as for example in Gardner, 2009.

Reasons for students’ drop out as perceived by faculty members versus as perceived by students (data from Gardner, 2009, as reported in Sverdlik et al., 2018, page 10):

|

Students’ attrition attributions |

lack of skills or motivation |

personal problems (e.g. work/life balance, family duties, mental illness) |

departmental challenges (incl. supervision, departmental politics) |

|

As seen by faculty members |

74% |

15% | |

|

As seen by PhD students |

21% |

34% |

30% |

In Gardner, 2009 we can read:

“That the student was lacking in ability, drive, focus, motivation, or initiative was cited most often by the faculty in this study as the reason for doctoral student departure”

and:

“Unlike any of the faculty members interviewed, students shared departmental issues as their second highest explanation for student departure”

Citing other papers which are in line with Gardner, 2009 findings, Sverdlik et al. conclude: “students often drop out of their graduate programs without providing an explanation to their department, thus contributing to the perception that attrition is the result of personal rather than departmental factors. This attributional perspective, in turn, can serve to discourage departmental reflection on the efficacy of existing structures or pursuing innovations that could benefit students.” (page 13)

To me it appears that lack of communication is going in every possible direction within academia:

“One issue that consistently arises is a mismatch in values and expectations between the student and the department, an unfortunate situation that can arise from departments not providing students with sufficient information at the admission stage regarding student roles and responsibilities” (page 13)

“Whereas most comments concerning supervisors were positive (e.g., joy) and acknowledged their efficiency, support, feedback, and demeanor, it was the discrepancy between supervisors’ and students’ expectations that generated confusion, stress, and anxiety in students.” (page 10)

Worth noting for students in STEM disciplines, such as myself: “the importance of supervisory fit is particularly evident in STEM disciplines where students’ research efforts (including their dissertation) are more closely intertwined with the work of their supervisors” (page 10)

Further in Sverdlik et al. we can find something else which I experienced myself:

“Although a mentorship or apprenticeship relationship with one’s supervisor has been found to be ideal for doctoral student satisfaction, findings also indicate that this intensive, hands-on supervision method is not necessarily required to maintain student well-being.” (page 10)

“These findings once again underscore the discrepancy between what doctoral students seek as the ideal supervisory relationship (e.g., a mentor who will closely guide them through every stage of the doctoral process) and what is empirically shown to correlate with satisfaction and progress (e.g., a supervisor who is responsive in time of need while allowing the formation of independence in the research process).” (page 11)

Indeed, when a professional relationship isn’t working well, responsibility is shared, and students also have their role to play:

“While most of the studies discussed above focus primarily on the responsibility of the supervisor to create and maintain a satisfying experience for their students, recent work has increasingly focused on factors that are under the control of students themselves (e.g., bringing positivity and respect into the relationship, practicing and demonstrating gratitude)” (page 11)

One more point which I can relate with: “a less commonly explored dynamic in the supervision experience is the compatibility between supervisees (i.e., students having the same supervisor). [] supervisee incompatibility in terms of skill, motivation, openness to feedback, etc. was found to significantly alter the content and process of supervision.” (page 10)

Something which I find frustrating in papers like Sverdlik et al. is a lack of concrete advice on how to improve, for example, the communication between supervisors and students, but I do understand that one cannot include everything in one (already quite long) paper and that it wasn’t this review’s aim. Nevertheless, in this paper one can still find a few suggestions of concrete action to implement, for example by departmental structure:

“[Studies] identified five ways in which departments, through their actors and cultures, empowered students’ agency: they approve of multiple career paths (e.g., academic and non-academic), provide opportunities to practice skills in diverse and authentic contexts, provide resources (financial and informational), facilitate networking within the department (e.g., organize orientation week activities to introduce students to one another and to faculty members), and facilitate accessible and supportive supervision.” (pages 12-13)

Or here about introducing communities of practice:

“Shacham and Od-Cohen (2009) examined the experiences and learning outcomes of doctoral students after participating in communities of practice (CoP), in which students frequently worked in small group with other doctoral students and supervisors to develop ideas, share challenges and successes, and receive feedback on research projects (including the dissertation). The authors found that students preferred the face-to-face communication, with the ability to share ideas, struggles, and coping strategies being a significant contributor to learning for these students. Students also indicated that they adopted reflective thinking habits, became more open to criticism, and gained a better understanding of concepts and ideas in their field through CoP participation.” (pages 14-15)

In conclusion to this part about external factors, I feel that Sverdlik et al. make an appropriate portrait of the academic world, reporting a serious lack of communication about expectations, values and other professional standards, and which results in profound misunderstandings between students, supervisors and departments. Sverdlik et al. consider different points of view and remind each party of their responsibilities.

2. Internal Factors — Motivation, Writing Skills and Regulatory Strategies

Motivation

When I first saw that the paper was talking about motivation, I got really curious. I thought, “there are so many factors influencing it! It can’t only be an internal factor, it’s so much affected by the people we work with!” Yes, indeed, and this is even better explained by the authors:

“Correlates of student motivation include a variety of inter- and intrapersonal factors, such as: age, personal goals, socialization, and fit with supervisor.” (table 2, page 7)

“Doctoral student motivation has also been found to be affected by external factors such as family support, socialization, collaborative learning, and fit with supervisor.” (page 16)

I like this sentence a lot: “Due to the increasingly unstructured nature of doctoral work, students are required to self-regulate their motivation to be successful completers of their programs.” (table 2, page 7)

And if, like me, you’re wondering how to translate this more concretely, have a look at this paragraph:

“Geraniou (2010) identified two broad classes of “survival strategies” used by doctoral students to maintain their motivation throughout their degree. The first set of internal survival strategies included self-reliance (e.g., reminding yourself that you can overcome obstacles), interest (e.g., reflecting on whether personal interests are aligned with scholarly activities), and achievement (e.g., focusing on the desire to achieve a doctoral degree); these strategies are shown in further research to correlated positively with satisfaction and persistence despite student obstacles. In contrast, external survival strategies involved motivating oneself through discussion (i.e., purposeful social support with peers, supervisors, or other faculty, such as advice seeking), as well as application, with the latter involving students applying relevant literatures (e.g., trying a new teaching strategy based on peer-reviewed research) or gaining confidence by engaging in scholarly activities (e.g., presenting or publishing personal research).” (pages 16-17)

Moreover, as we saw with the above table about the reasons for students dropping out of their programs, both supervisors and students mentioned lack of motivation. However, Gardner (2009) writes that “[students’] lack of motivation was strikingly different from the faculty members’ idea of a lack of motivation.” Indeed, in this paper, faculty members’ idea of students’ lack of motivation seemed to be about a lack of skills, a lack of intellectual capacity, or unwillingness to put on the work load. On the other hand, students described lack of motivation as arising from self-doubt of whether doing a PhD was the right professional choice for them, or whether this particular department or supervisor was a good fit for them. “In this way, the students did not feel, as the faculty did, that the students ‘‘should not have come in the first place’’ but rather that this experience helped them to find out what it was that they really did want to do” (Gardner, 2009).

So here again we see a mismatch between supervisors and students’ views, where students questioning their own life choice is perceived as a lack of skills by supervisors. My take-home message from this part about motivation would be that taking time to reflect on your motivation, and your colleagues’ motivation, asking yourself what to do to “self-regulate” it, might turn out to be one of the keys to survive graduate school. And once again communication is crucial.

Writing Skills

An interesting point here about writing. Again, something which I experienced myself in my PhD and which only reflected expectations mismatch:

“Aitchison et al. (2012) argued that students are emotionally attached to their writing and perceive it as part of their developing scholarly identities. For supervisors, on the other hand, writing was perceived as a means to an end, with the end being dissemination of research and contribution to their field. This discrepancy in the meaning of writing was further observed to lead to a lack of support and high expectations from supervisors, thus enhancing students’ emotional experiences.” (page 17)

Feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy

In addition to being interconnected with motivation, these two points are parts of the academic identity factor: “Academic identity refers to the ways in which students perceive themselves within their scholarly communities” (page 18)

“elevation/depression cycles [were] observed, with numerous students reporting significant fluctuations in self-worth throughout their studies (e.g., at times feeling competent and powerful, at other times feeling frustrated and helpless)” (page 19)

“Other studies further suggest that doctoral students are often overly ambitious early in their doctoral program, and thus tend to more strongly associate external processes (e.g., reviewer criticism) with their self-worth” (page 19)

Self-efficacy is defined here as “one’s confidence in successfully performing tasks associated with conducting research” (page 19)

“doctoral students with lower levels of self-efficacy are more likely to engage in self-handicapping behaviors so as to avoid being perceived (or perceiving themselves) as incompetent. [For example] overcommitment, busyness (appearing extremely busy when actually engaging with low-priority tasks), perfectionism, procrastination, disorganization, low effort, and choosing performance-debilitating circumstances (e.g., trying to work in a noisy location). Similarly, Ahern and Manathunga (2004) identified regularly changing one’s thesis topic or objectives, avoiding communication with one’s supervisor [] as well as delaying submitting work for review to reflect specific doctoral student self-handicapping (stalling) behaviors.” (page 20)

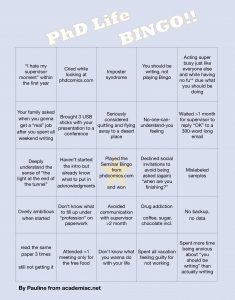

Reading this part was quite funny for me. While I consider myself as relatively well organized and productive, I do tend to make myself (unconsciously?) busy with low-priority tasks, this not only makes me look busy but participates in perfectionism and procrastination. I also tried to work in a noisy location but I learned from my mistake, and I even had about 3-4 months when I avoided my supervisor 🙂 Oh and did I mention that I was “overly ambitious” when I started my PhD? PhD Life Bingo? play here =>

Conclusion

In one summary sentence: “The most notable external factors affecting doctoral students’ experiences include supervision, their personal and social lives, departmental support and socialization, as well as financial opportunities. In contrast, the most significantly contributing internal factors included motivational variables as well as writing competencies and academic identity.” (page 20)

For me, this paper condenses many key concepts for professional integrity in academia and therefore it creates a set of best practices. It reminds each party (departments, supervisors, students) of their responsibilities. It draws attention on points which each party should pay attention to and it even provides some ideas of concrete actions to implement.

Please remember that in this blog post I skipped some parts, even highly important ones like the part about personal and social lives. Therefore, I strongly recommend having a look at the paper by yourself, for example by reading the table 2 (pages 5 to 8) which provide a great summary of their main findings.

Now that we understood what some of the main factors influencing doctoral students’ success and well-being are, what can we do concretely to help? Well, there are tons of things to try, here my little contributions so far:

- a checklist to help clarify supervisors and students’ expectations, to promote communication and improve understanding

- a resource of project management techniques to help supervisors and students finding ways to work together, as a team

- many resources to help PhD students and postdocs in Switzerland 🇨🇭 with the career question

- and I would like to remind again the importance of supervisors and departments to actively communicate about opportunities for soft skills courses or coaching training for PhD students

If you’ve really read the whole blog post, thank you so much!!! 🙂 What do you think? What can we do concretely to help? Please tell me in the comments below 👇

Also stay tune and don’t miss my next articles!

Thanks for this précis. I have been coming to terms with thoughts and feelings related to my PhD experience, and this helped tease apart some of these (especially my less-than-stellar self-efficacy)

Hey, thanks so much for your comment 🙂 Yes, it’s the same for me. Actually when I started reading this paper I didn’t expect that it would make me reflect so much on my PhD experience and that it would help me feel better about 🙂 That was a nice surprise!

Thank you so much for this review!! I loved what you highlighted, and will actually be taking both your blog post and the referenced article to my own research group as a “literature presentation.” I think that the component that brings in department structure is especially valuable as this is so frequently ignored when we try to consider improving overall PhD life. I also thought that your highlighting of the self-efficacy portion is really pertinent and often another aspect we sweep under the rug.

Thanks a lot for your comment! 🙂 I can’t express how happy I am to see people getting interested in my blog post, commenting on it and even wanted to use it in their research group! This means a lot to me, thank you 🙂

Yes about the department structure and the self-efficacy parts, I think that participate in making this review so important to the field and it’s definitely two aspects that we need to pay more attention to!